mandag den 17. oktober 2011

søndag den 16. oktober 2011

Afghan opium production 'rises by 61%' compared with 2010

Opium production in Afghanistan rose by an estimated 61% this year compared with 2010, according to a UN report.

The increase has been attributed to rising opium prices that have driven farmers to expand cultivation of the illicit opium poppy by 7% in 2011.

BBC.

lørdag den 15. oktober 2011

Persondyrkelse kontra tænkning.

I

"Det Kommunistiske Manifest" kan der ikke herske den store tvivl om, at Marx

agiterer for en autoritær samfundsorden, organiseret på statsligt

niveau. Efter revolutionen skal proletariatets diktatur "centralisere

alle produktionsinstrumenter i statens hænder", foretage en

"centralisering af kreditten i statens hænder ved hjælp af en nationalbank med statskapital og absolut monopol" samt foretage en "centralisering af

transportvæsenet i statens hænder", mens det hedder sig, at man skal

indføre "lige arbejdstvang for alle" og der desuden opfordrers til

"oprettelse af industrielle armeer, særlig indenfor landbruget".

Om dette skrev Bakunin i 1873: "The leaders of the Communist Party, namely Mr. Marx and his followers, will concentrate the reins of government in a strong hand. They will centralize all commercial, industrial, agricultural, and even scientific production, and then divide the masses into two armies — industrial and agricultural — under the direct command of state engineers, who will constitute a new privileged scientific and political class."

Er der her tale om et uretfærdigt angreb på en politisk modstander eller snarere om hvad man retmæssigt kan udlede af Marx' egne ord i "Det Kommunistiske Manifest"? Det forekommer åbenlyst, at der er tale om det sidste, idet det vist giver sig selv, at såfremt staten råder over alle produktionsinstrumenterne, transporten og kreditten og tvinger folk til at arbejde (for staten), så har staten arbejderklassen i et jerngreb.

At man også kan påvise visse autoritære elementer i Bakunins tænkning er knap så interessant, vil jeg tillade mig at mene, idet Bakunin overhovedet ikke spiller samme rolle i anarkismen (eller historien) som Marx gør i marxismen. Der er ikke, så vidt vides, nogen indflydelsesrig og levende anarkistisk retning som kalder sig bakunisme. Bakunin var desuden også glødende antisemitisk i nogle tekster, hvilket der ikke er nogen grund til at forsvare eller tale udenom, med mindre man gør sig i persondyrkelse.

Hos folk med en enorm skriftlig produktion kan man ofte finde selvmodsigelser og agitation for modsatrettede tanker. I Marx' tekster kan man således finde både libertære og autoritære tanker. I sidste ende er det væsentlige imidlertid nok, hvilke skrifter der har haft mest indflydelse på historiens gang og der hersker her ikke den store tvivl om, at Marx' autoritære side har haft mere indflydelse på historien, end hans mere libertære side. Den anarkistiske filosof Crispin Sartwell, som mener at Marx var en langt bedre tænker end Bakunin, er her værd at citere:

Om dette skrev Bakunin i 1873: "The leaders of the Communist Party, namely Mr. Marx and his followers, will concentrate the reins of government in a strong hand. They will centralize all commercial, industrial, agricultural, and even scientific production, and then divide the masses into two armies — industrial and agricultural — under the direct command of state engineers, who will constitute a new privileged scientific and political class."

Er der her tale om et uretfærdigt angreb på en politisk modstander eller snarere om hvad man retmæssigt kan udlede af Marx' egne ord i "Det Kommunistiske Manifest"? Det forekommer åbenlyst, at der er tale om det sidste, idet det vist giver sig selv, at såfremt staten råder over alle produktionsinstrumenterne, transporten og kreditten og tvinger folk til at arbejde (for staten), så har staten arbejderklassen i et jerngreb.

At man også kan påvise visse autoritære elementer i Bakunins tænkning er knap så interessant, vil jeg tillade mig at mene, idet Bakunin overhovedet ikke spiller samme rolle i anarkismen (eller historien) som Marx gør i marxismen. Der er ikke, så vidt vides, nogen indflydelsesrig og levende anarkistisk retning som kalder sig bakunisme. Bakunin var desuden også glødende antisemitisk i nogle tekster, hvilket der ikke er nogen grund til at forsvare eller tale udenom, med mindre man gør sig i persondyrkelse.

Hos folk med en enorm skriftlig produktion kan man ofte finde selvmodsigelser og agitation for modsatrettede tanker. I Marx' tekster kan man således finde både libertære og autoritære tanker. I sidste ende er det væsentlige imidlertid nok, hvilke skrifter der har haft mest indflydelse på historiens gang og der hersker her ikke den store tvivl om, at Marx' autoritære side har haft mere indflydelse på historien, end hans mere libertære side. Den anarkistiske filosof Crispin Sartwell, som mener at Marx var en langt bedre tænker end Bakunin, er her værd at citere:

The project of making [..] Marx come out as right as possible is a silly project, and one entirely unworthy of an actual thinker. Take what's right; reject the rest. Why not? Why not just say he's wrong about "industrial armies" etc., but right about x, y, and z? Why? because you're a follower not a philosopher. In which case, I don't actually need to read what you write or think about what you say. [...] You should read Marx exactly like you read any arguments, accounts, assertions: critically. You should take what you can use or what you can argue for or what works and leave all the rest without a moment's hesitation. [...] Don't defend Marx at all costs, or at any cost at all: take what's right and leave what's not: it doesn't matter. Marx is dead; he's not going to be impressed that you agree with him. [marxism] is supposed to be some kind of philosophy, science, history: not a religion that demands you're unquestioning capitulation to its myriad absurdities.Hvis en politisk filosofi degenererer til persondyrkelse af ideologiske patriarker, ophører den med at være filosofi, idet tænkningens ædle kunst af nødvendighed må være funderet på spørgen og tvivlen, hvorfor tænkningen altså må betegnes som grundlæggende anti-autoritær. I modsætning hertil har vi overbevisningen, som er kendetegnet ved, at al tvivl og spørgen er bragt til ophør. Den som med næb og klør forsvarer sine ideologiske overbevisningers ophavsmænd, selv når de kommer med de mest menneskefjendske argumenter, er snarere overbevist som religiøse mennesker, end tvivlende og spørgende, som tænkende mennesker. I stedet for overbevisningens fangenskab indenfor en given ideologisk matrices perspektiv, bør vi kultivere en sund skepsis overfor ethvert perspektiv som postulerer at være det eneste sande. Emancipation foregår ikke kun på det sociale/intersubjektive plan, med ligeledes på det kognitive/subjektive plan.

Michael Moore: Why the Occupy Wall Street Movement Can't Be Stopped.

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

fredag den 14. oktober 2011

Vi er forandringen. Vi er det nye alternativ.

Vi ser ingen positiv fremtid i en økonomi baseret på spekulanter og købmænd som kun tænker på at tjene penge, uden hensyn til andre menneskers og naturens behov. Vi ønsker en økonomi der tjener mennesket på en bæredygtig og retfærdig måde. En økonomi som er til gavn for alle, i stedet for som nu, hvor alt for mange tjener en uretfærdig og ubæredygtig økonomi, der mestendels er til gavn for de få.

Vi ser friheden som en af de vigtigste drivkræfter i den positive udvikling af menneskeheden og ønsker derfor et samfund hvor den enkelte har den størst mulige frihed til at gøre som han eller hun måtte ønske, så længe disse handlinger ikke skader andres muligheder for at gøre som de ønsker. Vores frihed slutter hvor andres frihed begynder. Vælger vi at følge denne enkle læresætning i vores liv vil meget være opnået.

Vi mener at sammenhold og solidaritet er vigtige forudsætninger for en positiv, kollektiv udvikling af vores fællesskaber og opfordrer derfor alle til at være solidariske, samarbejdende og delende i alle livets mange rum. Hver for sig er vi svage og skrøbelige enkeltpersoner. Kun ved at stå sammen, samarbejde og dele livets glæder, opnår vi den nødvendige styrke til at skabe positiv kollektiv forandring.

Vi ser frem til at dele fremtidens fællesskaber med mennesker, der ligesom os, mest af alt blot ønsker at være frie og elskede og som derfor giver andre mennesker plads til at være frie, elskede og elskende. Kærligheden og friheden er de vigtigste kræfter i verden. Med dem er vi uendeligt stærke og ressourcefulde, mens vi uden dem er arme stakler på fast kurs mod undergangen. Det er derfor på høje tid at vi lader kærligheden og friheden vinde over frygten og dens nære slægtning - den usikre, barnlige egoisme.

Vi ønsker et samfund hvor der er frihed til forskellighed og hvor mange farver på paletten betragtes som en rigdom og en styrke. Vi anser mangfoldighed og åbenhed overfor andre perspektiver på tilværelsen end vores egne for en uvurderlig styrke. Vi ønsker derfor et samfund hvor der er plads til diversitet.

Vi mener det er af højeste vigtighed, at vi værner om den natur som garanterer vores overlevelse og som eneste dag forsyner os med produkter som er vigtige for vores overlevelse. Vi anser derfor bæredygtighed og styrkelser af naturen for at være nødvendige forudsætninger for en positiv kollektiv nutid og fremtid ifælleskab på planeten Jorden.

Vi er trætte af at blive domineret af mennesker, som mener de er bedre egnet end os til at træffe væsentlige beslutninger, som påvirker vores allesammens dagligdag. Vi ønsker direkte indflydelse på måden hvorpå vores fællesskaber indrettes og styres og vi ønsker derfor muligheden for, at være medbestemmende og medstyrende i alle de institutioner som vi, vores forældre og børn, befinder os i.

Vi ser friheden som en af de vigtigste drivkræfter i den positive udvikling af menneskeheden og ønsker derfor et samfund hvor den enkelte har den størst mulige frihed til at gøre som han eller hun måtte ønske, så længe disse handlinger ikke skader andres muligheder for at gøre som de ønsker. Vores frihed slutter hvor andres frihed begynder. Vælger vi at følge denne enkle læresætning i vores liv vil meget være opnået.

Vi mener at sammenhold og solidaritet er vigtige forudsætninger for en positiv, kollektiv udvikling af vores fællesskaber og opfordrer derfor alle til at være solidariske, samarbejdende og delende i alle livets mange rum. Hver for sig er vi svage og skrøbelige enkeltpersoner. Kun ved at stå sammen, samarbejde og dele livets glæder, opnår vi den nødvendige styrke til at skabe positiv kollektiv forandring.

Vi ser frem til at dele fremtidens fællesskaber med mennesker, der ligesom os, mest af alt blot ønsker at være frie og elskede og som derfor giver andre mennesker plads til at være frie, elskede og elskende. Kærligheden og friheden er de vigtigste kræfter i verden. Med dem er vi uendeligt stærke og ressourcefulde, mens vi uden dem er arme stakler på fast kurs mod undergangen. Det er derfor på høje tid at vi lader kærligheden og friheden vinde over frygten og dens nære slægtning - den usikre, barnlige egoisme.

Vi ønsker et samfund hvor der er frihed til forskellighed og hvor mange farver på paletten betragtes som en rigdom og en styrke. Vi anser mangfoldighed og åbenhed overfor andre perspektiver på tilværelsen end vores egne for en uvurderlig styrke. Vi ønsker derfor et samfund hvor der er plads til diversitet.

Vi mener det er af højeste vigtighed, at vi værner om den natur som garanterer vores overlevelse og som eneste dag forsyner os med produkter som er vigtige for vores overlevelse. Vi anser derfor bæredygtighed og styrkelser af naturen for at være nødvendige forudsætninger for en positiv kollektiv nutid og fremtid ifælleskab på planeten Jorden.

Vi er trætte af at blive domineret af mennesker, som mener de er bedre egnet end os til at træffe væsentlige beslutninger, som påvirker vores allesammens dagligdag. Vi ønsker direkte indflydelse på måden hvorpå vores fællesskaber indrettes og styres og vi ønsker derfor muligheden for, at være medbestemmende og medstyrende i alle de institutioner som vi, vores forældre og børn, befinder os i.

mandag den 10. oktober 2011

fredag den 23. september 2011

Kropotkin: Appeal to the Young.

Don't let anyone tell us that we—but a small band—are

too weak to attain unto the magnificent end at which we aim.

Count and see how many there are who suffer this injustice.

We peasants who work for others, and who mumble the

straw while our master eats the wheat, we by ourselves are

millions.

We workers who weave silks and velvet in order that we

may be clothed in rags, we, too, are a great multitude; and

when the clang of the factories permits us a moments repose,

we overflow the streets and squares like the sea in a

spring tide.

We soldiers who are driven along to the word of command,

or by blows, we who receive the bullets for which our

officers get crosses and pensions, we, too, poor fools who have

hitherto known no better than to shoot our brothers, why we

have only to make a right about face towards these plumed

and decorated personages who are so good as to command

us, to see a ghastly pallor overspread their faces.

Aye, all of us together, we who suffer and are insulted

daily, we are a multitude whom no one can number, we are

the ocean that can embrace and swallow up all else. When

we have but the will to do it, that very moment will justice

be done: that very instant the tyrants of the earth shall bite

the dust.

- Pyotr Kropotkin, "An Appeal to the Young," 1880

too weak to attain unto the magnificent end at which we aim.

Count and see how many there are who suffer this injustice.

We peasants who work for others, and who mumble the

straw while our master eats the wheat, we by ourselves are

millions.

We workers who weave silks and velvet in order that we

may be clothed in rags, we, too, are a great multitude; and

when the clang of the factories permits us a moments repose,

we overflow the streets and squares like the sea in a

spring tide.

We soldiers who are driven along to the word of command,

or by blows, we who receive the bullets for which our

officers get crosses and pensions, we, too, poor fools who have

hitherto known no better than to shoot our brothers, why we

have only to make a right about face towards these plumed

and decorated personages who are so good as to command

us, to see a ghastly pallor overspread their faces.

Aye, all of us together, we who suffer and are insulted

daily, we are a multitude whom no one can number, we are

the ocean that can embrace and swallow up all else. When

we have but the will to do it, that very moment will justice

be done: that very instant the tyrants of the earth shall bite

the dust.

- Pyotr Kropotkin, "An Appeal to the Young," 1880

tirsdag den 20. september 2011

David Graeber Interview on RT

Dokumentar: Garbage Warrior.

mandag den 19. september 2011

Autoritær socialisme er statskapitalisme.

Begrebet socialisme synes at implicere, at der er tale om et prosocialt snarere end om et asocialt fænomen og det er derfor nok på sin plads, at forsøge at komme med et gangbart bud på hvad begrebet social implicerer. Ordet kommer af det latinske socialis som knytter sig til det ligeledes latinske socius der betyder følgesvend, men fortæller de etymologiske rødder os noget om, hvad det sociale er indbegrebet af?

Mellem to følgesvende er der snarere tale om et nogenlunde lige forhold, end der er tale om et forhold karakteristisk ved, at den ene part dominerer den anden og påtvinger denne sine meninger og præferencer. At følges ad implicerer noget jævnbyrdigt, mens at følge efter, eller at følge ordrer, nok nærmere implicerer det modsatte.

Ordet social har altså derfor sine sproglige rødder i noget der nok ikke ligger væk langt fra hvad de fleste vel mener når de taler om, at en person er et meget socialt væsen. For når vi synes at nogen handler socialt, mener vi vel i reglen, at vedkommende handler på en måde som er opretholdende for det sociale forhold, ved at give plads til den anden, i stedet for at dominere ham eller hende. Modsat mener vi vel ofte, når vi taler om at en person handler asocialt, at vi har at gøre med et menneske som ikke giver plads til sine medmennesker, men som i stedet forsøger at påtvinge dem sine egne egoistiske præferencer. Den asociale handler altså på en måde der er ødelæggende for det sociale forhold, mens den sociale opretholder og styrker det.

Ovenstående forsøg på en indkredsning af hvad der kendetegner det sociale, som et kendetegn ved socialisme, er imidlertid vanskeligt foreneligt med det meste af den statsindlejrede og autoritære socialisme vi har været og fortsat er vidner til. Den autoritære, statsopretholdende - eller endda statsekspanderende - variant af socialismen er en selvmodsigelse.

Ønsker man, som mange venstreorienterede påstår, at destruere klassesamfundets indbyggede sociale uligheder, er svaret derfor ikke mere stat, men mindre. I et samfund hvor staten overtager alle produktionsmidlerne bliver alle - undtagen de som styrer staten - gjort til proletarer og man har således ikke forringet, endsige destrueret, klassesamfundets uretfærdige og asociale dominansstrukturer, men derimod gjort dem endnu mere omfattende qua proletariseringen af alle. Den herskende kapitalistiske klasse er godt nok blevet sendt hen hvor peberet gror, men erstatningen, i form af en herskende statslig klasse, kan ikke siges at have elimineret kapitalismens indbyggede autoritære og derfor asociale uretfærdighed. Uretfærdigheden har blot fået et andet navn.

Hvis socialismens mål er etableringen af gunstige, frigjorte og sociale forhold for arbejderne på deres arbejdspladser, realiseres dette derfor ikke ved at udskifte et autoritært og således asocialt forhold med et andet, for hvilken frigørelse fra det autoritære og asociale klassesamfunds snærende bånd skulle man derved have opnået? Arbejdernes fælles ejerskab af produktionsmidlerne står altså derfor i skarp kontrast til et statsligt ejerskab af disse. I første tilfælde ejes og forvaltes produktionsmidlerne kollektivt af arbejderne selv i en ikke-hierarkisk og horisontal organisationsstruktur. I det andet ejes og forvaltes produktionsmidlerne af nationalstaten i en hierarkisk og vertikal organisationsstruktur, idet disse er statens organisatoriske kendetegn. Når arbejderne kollektivt ejer og forvalter produktionsmidlerne på en ikke-hierarkisk og horisontal måde er der endvidere tale om en strukturel decentralisering, mens der i det nationalstatsejede tilfælde, i modsætning hertil, er tale om en strukturel centralisering, da staten per definition er et centralistisk fænomen.

Nationaliseringer af produktionsmidlerne kan derfor ikke siges at være prosociale, men må snarere siges at være asociale, idet der er tale om en styrkelse af det autoritære og socialt ulige forhold som den autoritære og vertikale stats organisatoriske struktur implicerer. Overtager staten produktionsmidlerne foretages der derfor ikke et egentligt opgør med kapitalismen. Det er blot tale om et skift fra en privatejet kapitalisme til en statsejet. Statssocialismen kan derfor vanskeligt siges at leve op til den ligebyrdige socialitet som begrebet socialisme synes at implicere, men må snarere siges at undergrave denne ligebyrdighed ved at fortsætte den asociale, hierarkiske og dominansorienterede kapitalisme, blot med andre midler og under andre ejerskabsformer.

Etiketter:

anarkisme,

decentralisme,

kritik af centralisme,

nationaliseringer,

proletarisering,

socialisme

tirsdag den 13. september 2011

Tænk hvis....

Tænk hvis alle centrale magtformer var blevet sendt hen hvor peberet gror i 1900. Det kan let tænkes at verden i så fald ville have været lykkeligt foruden rigtig mange sørgelige fænomener og begivenheder. Uden centrale magtformer...

- Ingen grænser.

- Ingen verdenskrige, kold krig eller andre statsligt funderede krige.

- Ingen atomvåben og mutually assured destruction.

- Ingen subsidiering af våbensektoren og sandsynligvis meget mindre oprustning.

- Ingen arbejds- og udryddelseslejre.

- Ingen Holocaust, Halabja eller Hiroshima.

- Ingen stalinisme, maoisme, nazisme, fascisme eller neoliberalisme.

- Ingen systematisk tortur begået i statsligt regi.

- Ingen magtfulde efterretningstjenester og politistater.

- Ingen topstyrede militære organisationer.

- Ingen administrativ uigennemsigtighed.

- Ingen centrale statslige propagandaorganer.

- Ingen centralbanker eller centraladministrationer.

- Ingen politikere eller embedsmænd.

- Ingen kriminalisering af offerløse handlinger.

- Ingen tvangsskoling, tvangsaktivering eller værnepligt.

- Ingen EU, NATO eller Amerikansk imperialisme.

- Ingen OPEC, Verdensbank, IMF eller WTO.

- Ingen transnationale selskaber eller globaliseret kapitalisme.

Etiketter:

anarkisme,

decentralisme,

kritik af centralisme

mandag den 12. september 2011

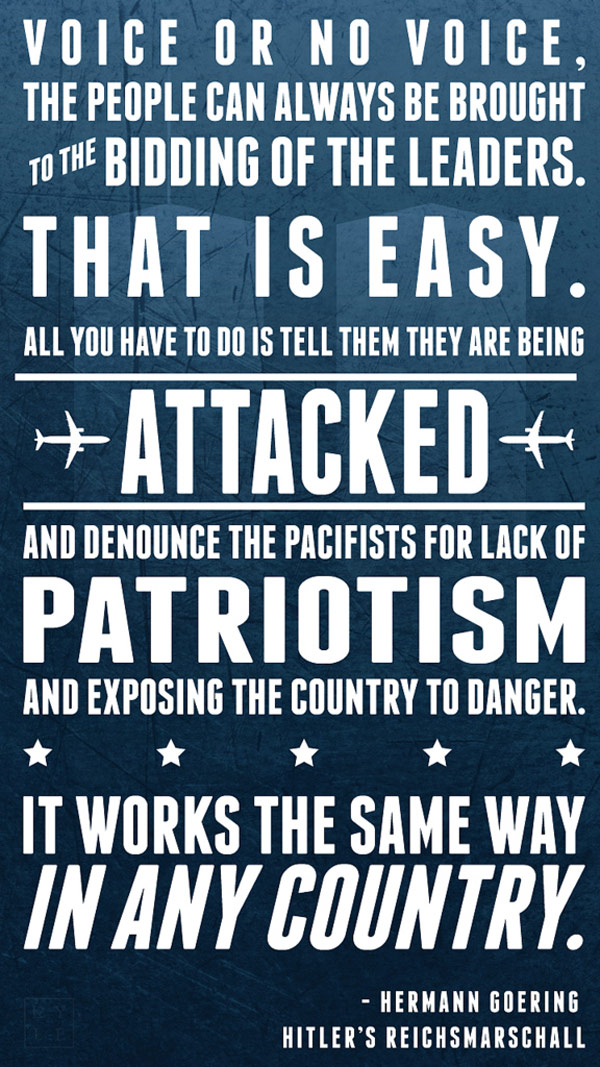

Dagens Citat: Hermann Göring

Dagens Citat: Noam Chomsky.

"Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions. In the Western world, at least, they have the power that comes from political liberty, from access to information and freedom of expression. For a privileged minority, Western democracy provides the leisure, the facilities, and the training to seek the truth lying hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation, ideology and class interest, through which the events of current history are presented to us."

The Responsibility of Intellectuals.

lørdag den 10. september 2011

"In most important ways you are probably already an anarchist — you just don’t realize it."

Are You An Anarchist?

by David Graeber.

Chances are you have already heard something about who anarchists are and what they are supposed to believe. Chances are almost everything you have heard is nonsense. Many people seem to think that anarchists are proponents of violence, chaos, and destruction, that they are against all forms of order and organization, or that they are crazed nihilists who just want to blow everything up. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Anarchists are simply people who believe human beings are capable of behaving in a reasonable fashion without having to be forced to. It is really a very simple notion. But it’s one that the rich and powerful have always found extremely dangerous.

At their very simplest, anarchist beliefs turn on to two elementary assumptions. The first is that human beings are, under ordinary circumstances, about as reasonable and decent as they are allowed to be, and can organize themselves and their communities without needing to be told how. The second is that power corrupts. Most of all, anarchism is just a matter of having the courage to take the simple principles of common decency that we all live by, and to follow them through to their logical conclusions. Odd though this may seem, in most important ways you are probably already an anarchist — you just don’t realize it.

Let’s start by taking a few examples from everyday life:

If there’s a line to get on a crowded bus, do you wait your turn and refrain from elbowing your way past others even in the absence of police?

If you answered “yes”, then you are used to acting like an anarchist! The most basic anarchist principle is self-organization: the assumption that human beings do not need to be threatened with prosecution in order to be able to come to reasonable understandings with each other, or to treat each other with dignity and respect.

Everyone believes they are capable of behaving reasonably themselves. If they think laws and police are necessary, it is only because they don’t believe that other people are not. But if you think about it, don’t those people all feel exactly the same way about you? Anarchists argue that almost all the anti-social behavior which makes us think it’s necessary to have armies, police, prisons, and governments to control our lives, is actually caused by the systematic inequalities and injustice those armies, police, prisons and governments make possible. It’s all a vicious circle. If people are used to being treated like their opinions do not matter, they are likely to become angry and cynical, even violent — which of course makes it easy for those in power to say that their opinions do not matter. Once they understand that their opinions really do matter just as much as anyone else’s, they tend to become remarkably understanding. To cut a long story short: anarchists believe that for the most part it is power itself, and the effects of power, that make people stupid and irresponsible.

Are you a member of a club or sports team or any other voluntary organization where decisions are not imposed by one leader but made on the basis of general consent?

If you answered “yes”, then you belong to an organization which works on anarchist principles! Another basic anarchist principle is voluntary association. This is simply a matter of applying democratic principles to ordinary life. The only difference is that anarchists believe it should be possible to have a society in which everything could be organized along these lines, all groups based on the free consent of their members, and therefore, that all top-down, military styles of organization like armies or bureaucracies or large corporations, based on chains of command, would no longer be necessary. Perhaps you don’t believe that would be possible. Perhaps you do. But every time you reach an agreement by consensus, rather than threats, every time you make a voluntary arrangement with another person, come to an understanding, or reach a compromise by taking due consideration of the other person’s particular situation or needs, you are being an anarchist — even if you don’t realize it.

Anarchism is just the way people act when they are free to do as they choose, and when they deal with others who are equally free — and therefore aware of the responsibility to others that entails. This leads to another crucial point: that while people can be reasonable and considerate when they are dealing with equals, human nature is such that they cannot be trusted to do so when given power over others. Give someone such power, they will almost invariably abuse it in some way or another.

Do you believe that most politicians are selfish, egotistical swine who don’t really care about the public interest? Do you think we live in an economic system which is stupid and unfair?

If you answered “yes”, then you subscribe to the anarchist critique of today’s society — at least, in its broadest outlines. Anarchists believe that power corrupts and those who spend their entire lives seeking power are the very last people who should have it. Anarchists believe that our present economic system is more likely to reward people for selfish and unscrupulous behavior than for being decent, caring human beings. Most people feel that way. The only difference is that most people don’t think there’s anything that can be done about it, or anyway — and this is what the faithful servants of the powerful are always most likely to insist — anything that won’t end up making things even worse.

But what if that weren’t true?

And is there really any reason to believe this? When you can actually test them, most of the usual predictions about what would happen without states or capitalism turn out to be entirely untrue. For thousands of years people lived without governments. In many parts of the world people live outside of the control of governments today. They do not all kill each other. Mostly they just get on about their lives the same as anyone else would. Of course, in a complex, urban, technological society all this would be more complicated: but technology can also make all these problems a lot easier to solve. In fact, we have not even begun to think about what our lives could be like if technology were really marshaled to fit human needs. How many hours would we really need to work in order to maintain a functional society — that is, if we got rid of all the useless or destructive occupations like telemarketers, lawyers, prison guards, financial analysts, public relations experts, bureaucrats and politicians, and turn our best scientific minds away from working on space weaponry or stock market systems to mechanizing away dangerous or annoying tasks like coal mining or cleaning the bathroom, and distribute the remaining work among everyone equally? Five hours a day? Four? Three? Two? Nobody knows because no one is even asking this kind of question. Anarchists think these are the very questions we should be asking.

Do you really believe those things you tell your children(or that your parents told you)?

It doesn’t matter who started it.” “Two wrongs don’t make a right.” “Clean up your own mess.” “Do unto others...” “Don’t be mean to people just because they’re different.” Perhaps we should decide whether we’re lying to our children when we tell them about right and wrong, or whether we’re willing to take our own injunctions seriously. Because if you take these moral principles to their logical conclusions, you arrive at anarchism.

Take the principle that two wrongs don’t make a right. If you really took it seriously, that alone would knock away almost the entire basis for war and the criminal justice system. The same goes for sharing: we’re always telling children that they have to learn to share, to be considerate of each other’s needs, to help each other; then we go off into the real world where we assume that everyone is naturally selfish and competitive. But an anarchist would point out: in fact, what we say to our children is right. Pretty much every great worthwhile achievement in human history, every discovery or accomplishment that’s improved our lives, has been based on cooperation and mutual aid; even now, most of us spend more of our money on our friends and families than on ourselves; while likely as not there will always be competitive people in the world, there’s no reason why society has to be based on encouraging such behavior, let alone making people compete over the basic necessities of life. That only serves the interests of people in power, who want us to live in fear of one another. That’s why anarchists call for a society based not only on free association but mutual aid. The fact is that most children grow up believing in anarchist morality, and then gradually have to realize that the adult world doesn’t really work that way. That’s why so many become rebellious, or alienated, even suicidal as adolescents, and finally, resigned and bitter as adults; their only solace, often, being the ability to raise children of their own and pretend to them that the world is fair. But what if we really could start to build a world which really was at least founded on principles of justice? Wouldn’t that be the greatest gift to one’s children one could possibly give?

Do you believe that human beings are fundamentally corrupt and evil, or that certain sorts of people (women, people of color, ordinary folk who are not rich or highly educated) are inferior specimens, destined to be ruled by their betters?

If you answered “yes”, then, well, it looks like you aren’t an anarchist after all. But if you answered “no”, then chances are you already subscribe to 90% of anarchist principles, and, likely as not, are living your life largely in accord with them. Every time you treat another human with consideration and respect, you are being an anarchist. Every time you work out your differences with others by coming to reasonable compromise, listening to what everyone has to say rather than letting one person decide for everyone else, you are being an anarchist. Every time you have the opportunity to force someone to do something, but decide to appeal to their sense of reason or justice instead, you are being an anarchist. The same goes for every time you share something with a friend, or decide who is going to do the dishes, or do anything at all with an eye to fairness.

Now, you might object that all this is well and good as a way for small groups of people to get on with each other, but managing a city, or a country, is an entirely different matter. And of course there is something to this. Even if you decentralize society and puts as much power as possible in the hands of small communities, there will still be plenty of things that need to be coordinated, from running railroads to deciding on directions for medical research. But just because something is complicated does not mean there is no way to do it democratically. It would just be complicated. In fact, anarchists have all sorts of different ideas and visions about how a complex society might manage itself. To explain them though would go far beyond the scope of a little introductory text like this. Suffice it to say, first of all, that a lot of people have spent a lot of time coming up with models for how a really democratic, healthy society might work; but second, and just as importantly, no anarchist claims to have a perfect blueprint. The last thing we want is to impose prefab models on society anyway. The truth is we probably can’t even imagine half the problems that will come up when we try to create a democratic society; still, we’re confident that, human ingenuity being what it is, such problems can always be solved, so long as it is in the spirit of our basic principles-which are, in the final analysis, simply the principles of fundamental human decency.

by David Graeber.

Chances are you have already heard something about who anarchists are and what they are supposed to believe. Chances are almost everything you have heard is nonsense. Many people seem to think that anarchists are proponents of violence, chaos, and destruction, that they are against all forms of order and organization, or that they are crazed nihilists who just want to blow everything up. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Anarchists are simply people who believe human beings are capable of behaving in a reasonable fashion without having to be forced to. It is really a very simple notion. But it’s one that the rich and powerful have always found extremely dangerous.

At their very simplest, anarchist beliefs turn on to two elementary assumptions. The first is that human beings are, under ordinary circumstances, about as reasonable and decent as they are allowed to be, and can organize themselves and their communities without needing to be told how. The second is that power corrupts. Most of all, anarchism is just a matter of having the courage to take the simple principles of common decency that we all live by, and to follow them through to their logical conclusions. Odd though this may seem, in most important ways you are probably already an anarchist — you just don’t realize it.

Let’s start by taking a few examples from everyday life:

If there’s a line to get on a crowded bus, do you wait your turn and refrain from elbowing your way past others even in the absence of police?

If you answered “yes”, then you are used to acting like an anarchist! The most basic anarchist principle is self-organization: the assumption that human beings do not need to be threatened with prosecution in order to be able to come to reasonable understandings with each other, or to treat each other with dignity and respect.

Everyone believes they are capable of behaving reasonably themselves. If they think laws and police are necessary, it is only because they don’t believe that other people are not. But if you think about it, don’t those people all feel exactly the same way about you? Anarchists argue that almost all the anti-social behavior which makes us think it’s necessary to have armies, police, prisons, and governments to control our lives, is actually caused by the systematic inequalities and injustice those armies, police, prisons and governments make possible. It’s all a vicious circle. If people are used to being treated like their opinions do not matter, they are likely to become angry and cynical, even violent — which of course makes it easy for those in power to say that their opinions do not matter. Once they understand that their opinions really do matter just as much as anyone else’s, they tend to become remarkably understanding. To cut a long story short: anarchists believe that for the most part it is power itself, and the effects of power, that make people stupid and irresponsible.

Are you a member of a club or sports team or any other voluntary organization where decisions are not imposed by one leader but made on the basis of general consent?

If you answered “yes”, then you belong to an organization which works on anarchist principles! Another basic anarchist principle is voluntary association. This is simply a matter of applying democratic principles to ordinary life. The only difference is that anarchists believe it should be possible to have a society in which everything could be organized along these lines, all groups based on the free consent of their members, and therefore, that all top-down, military styles of organization like armies or bureaucracies or large corporations, based on chains of command, would no longer be necessary. Perhaps you don’t believe that would be possible. Perhaps you do. But every time you reach an agreement by consensus, rather than threats, every time you make a voluntary arrangement with another person, come to an understanding, or reach a compromise by taking due consideration of the other person’s particular situation or needs, you are being an anarchist — even if you don’t realize it.

Anarchism is just the way people act when they are free to do as they choose, and when they deal with others who are equally free — and therefore aware of the responsibility to others that entails. This leads to another crucial point: that while people can be reasonable and considerate when they are dealing with equals, human nature is such that they cannot be trusted to do so when given power over others. Give someone such power, they will almost invariably abuse it in some way or another.

Do you believe that most politicians are selfish, egotistical swine who don’t really care about the public interest? Do you think we live in an economic system which is stupid and unfair?

If you answered “yes”, then you subscribe to the anarchist critique of today’s society — at least, in its broadest outlines. Anarchists believe that power corrupts and those who spend their entire lives seeking power are the very last people who should have it. Anarchists believe that our present economic system is more likely to reward people for selfish and unscrupulous behavior than for being decent, caring human beings. Most people feel that way. The only difference is that most people don’t think there’s anything that can be done about it, or anyway — and this is what the faithful servants of the powerful are always most likely to insist — anything that won’t end up making things even worse.

But what if that weren’t true?

And is there really any reason to believe this? When you can actually test them, most of the usual predictions about what would happen without states or capitalism turn out to be entirely untrue. For thousands of years people lived without governments. In many parts of the world people live outside of the control of governments today. They do not all kill each other. Mostly they just get on about their lives the same as anyone else would. Of course, in a complex, urban, technological society all this would be more complicated: but technology can also make all these problems a lot easier to solve. In fact, we have not even begun to think about what our lives could be like if technology were really marshaled to fit human needs. How many hours would we really need to work in order to maintain a functional society — that is, if we got rid of all the useless or destructive occupations like telemarketers, lawyers, prison guards, financial analysts, public relations experts, bureaucrats and politicians, and turn our best scientific minds away from working on space weaponry or stock market systems to mechanizing away dangerous or annoying tasks like coal mining or cleaning the bathroom, and distribute the remaining work among everyone equally? Five hours a day? Four? Three? Two? Nobody knows because no one is even asking this kind of question. Anarchists think these are the very questions we should be asking.

Do you really believe those things you tell your children(or that your parents told you)?

It doesn’t matter who started it.” “Two wrongs don’t make a right.” “Clean up your own mess.” “Do unto others...” “Don’t be mean to people just because they’re different.” Perhaps we should decide whether we’re lying to our children when we tell them about right and wrong, or whether we’re willing to take our own injunctions seriously. Because if you take these moral principles to their logical conclusions, you arrive at anarchism.

Take the principle that two wrongs don’t make a right. If you really took it seriously, that alone would knock away almost the entire basis for war and the criminal justice system. The same goes for sharing: we’re always telling children that they have to learn to share, to be considerate of each other’s needs, to help each other; then we go off into the real world where we assume that everyone is naturally selfish and competitive. But an anarchist would point out: in fact, what we say to our children is right. Pretty much every great worthwhile achievement in human history, every discovery or accomplishment that’s improved our lives, has been based on cooperation and mutual aid; even now, most of us spend more of our money on our friends and families than on ourselves; while likely as not there will always be competitive people in the world, there’s no reason why society has to be based on encouraging such behavior, let alone making people compete over the basic necessities of life. That only serves the interests of people in power, who want us to live in fear of one another. That’s why anarchists call for a society based not only on free association but mutual aid. The fact is that most children grow up believing in anarchist morality, and then gradually have to realize that the adult world doesn’t really work that way. That’s why so many become rebellious, or alienated, even suicidal as adolescents, and finally, resigned and bitter as adults; their only solace, often, being the ability to raise children of their own and pretend to them that the world is fair. But what if we really could start to build a world which really was at least founded on principles of justice? Wouldn’t that be the greatest gift to one’s children one could possibly give?

Do you believe that human beings are fundamentally corrupt and evil, or that certain sorts of people (women, people of color, ordinary folk who are not rich or highly educated) are inferior specimens, destined to be ruled by their betters?

If you answered “yes”, then, well, it looks like you aren’t an anarchist after all. But if you answered “no”, then chances are you already subscribe to 90% of anarchist principles, and, likely as not, are living your life largely in accord with them. Every time you treat another human with consideration and respect, you are being an anarchist. Every time you work out your differences with others by coming to reasonable compromise, listening to what everyone has to say rather than letting one person decide for everyone else, you are being an anarchist. Every time you have the opportunity to force someone to do something, but decide to appeal to their sense of reason or justice instead, you are being an anarchist. The same goes for every time you share something with a friend, or decide who is going to do the dishes, or do anything at all with an eye to fairness.

Now, you might object that all this is well and good as a way for small groups of people to get on with each other, but managing a city, or a country, is an entirely different matter. And of course there is something to this. Even if you decentralize society and puts as much power as possible in the hands of small communities, there will still be plenty of things that need to be coordinated, from running railroads to deciding on directions for medical research. But just because something is complicated does not mean there is no way to do it democratically. It would just be complicated. In fact, anarchists have all sorts of different ideas and visions about how a complex society might manage itself. To explain them though would go far beyond the scope of a little introductory text like this. Suffice it to say, first of all, that a lot of people have spent a lot of time coming up with models for how a really democratic, healthy society might work; but second, and just as importantly, no anarchist claims to have a perfect blueprint. The last thing we want is to impose prefab models on society anyway. The truth is we probably can’t even imagine half the problems that will come up when we try to create a democratic society; still, we’re confident that, human ingenuity being what it is, such problems can always be solved, so long as it is in the spirit of our basic principles-which are, in the final analysis, simply the principles of fundamental human decency.

torsdag den 8. september 2011

Percy Bysshe Shelley: "Song To The Men Of England"

Men of England, wherefore plough

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save,

From the cradle to the grave,

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat -nay, drink your blood?

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love's gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear?

The seed ye sow another reaps;

The wealth ye find another keeps;

The robes ye weave another wears;

The arms ye forge another bears.

Sow seed, -but let no tyrant reap;

Find wealth, -let no imposter heap;

Weave robes, -let not the idle wear;

Forge arms, in your defence to bear.

Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells;

In halls ye deck another dwells.

Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye see

The steel ye tempered glance on ye.

With plough and spade and hoe and loom,

Trace your grave, and build your tomb,

And weave your winding-sheet, till fair

England be your sepulchre!

For the lords who lay ye low?

Wherefore weave with toil and care

The rich robes your tyrants wear?

Wherefore feed and clothe and save,

From the cradle to the grave,

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat -nay, drink your blood?

Wherefore, Bees of England, forge

Many a weapon, chain, and scourge,

That these stingless drones may spoil

The forced produce of your toil?

Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,

Shelter, food, love's gentle balm?

Or what is it ye buy so dear

With your pain and with your fear?

The seed ye sow another reaps;

The wealth ye find another keeps;

The robes ye weave another wears;

The arms ye forge another bears.

Sow seed, -but let no tyrant reap;

Find wealth, -let no imposter heap;

Weave robes, -let not the idle wear;

Forge arms, in your defence to bear.

Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells;

In halls ye deck another dwells.

Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye see

The steel ye tempered glance on ye.

With plough and spade and hoe and loom,

Trace your grave, and build your tomb,

And weave your winding-sheet, till fair

England be your sepulchre!

Abonner på:

Opslag (Atom)